The latest report of the Hauraki Gulf Forum, the body set up to protect the magnificent Hauraki Gulf Marine Park, paints a sad picture of an environment which continues to deteriorate and a protective mechanism that is badly broken and in urgent need of repairs, writes Ray Buckmaster.

Witnessing the departure of a group of godwits on their northward migration provokes mixed emotions. On the one hand, their annual journeys from one end of the world to the other are truly awesome. On the other, it’s impossible not to wonder whether this amazing migration, which has been going on for at least ten thousand years, will be able to continue for ten thousand more.

First stop after Pukorokoro Miranda is the Yellow Sea where huge areas of habitat where birds used to refuel have been lost or degraded. Then it’s on to Alaska where the effects of climate change are much amplified. And there’s no room for complacency here, either, because the Firth of Thames has also suffered considerable human exploitation that has caused widespread environmental damage.

We know that some progress is being made in protecting the fringes of the Yellow Sea. But what about here? Are we making progress?

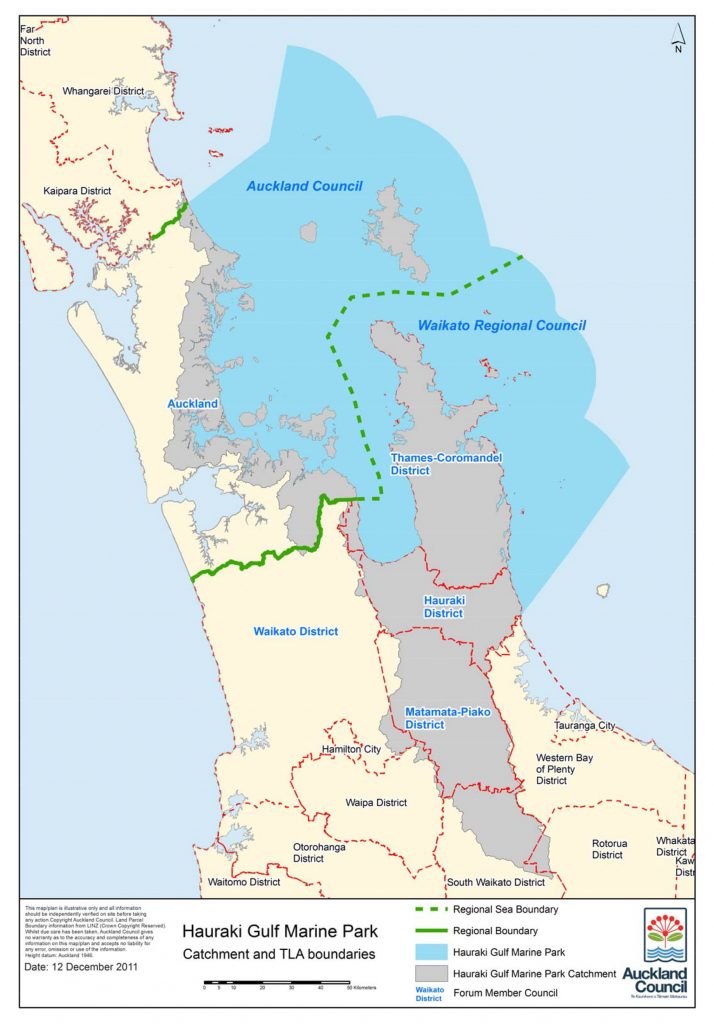

An answer to that question came a few weeks ago with the somewhat belated release of The State of Our Gulf 2017, the fifth in a series of triennial progress reports issued by the Hauraki Gulf Forum, the body charged with monitoring, managing and, hopefully, restoring the Hauraki Gulf of which the Firth of Thames is a vital part. The forum includes representatives from the manu whenua, the two major territorial authorities, Auckland Council and Waikato Regional Council, several district councils and various Government ministries.

As is always the case, there are areas of good news in the 2017 report as some challenges are less intractable than others.

- Great progress is being made in restoring seabird colonies, working cooperatively with the fishing industry to reduce seabird deaths and establishing pest free island sanctuaries.

- There is a splendid example of integrated management preserving the Bryde’s Whale population of the Waitemata Harbour. Whales were regularly coming into collision with cargo vessels but the ships now speed up before they reach the Gulf and slow down as they pass through it. It is a win-win situation where cargo vessels maintain the same transit time and whales can avoid collisions with the slower moving ships.

- There are now 46 islands free of mammalian pests which form critical sanctuaries for many endangered native species. Significant progress is being made in the revegetation of the larger islands, and the restoration of functioning indigenous ecosystems, often in community-led programmes.

Overall, though, successive reports of the Hauraki Gulf Forum have noted a continued downturn in significant environmental indicators and acknowledged that there is no simple solution to halting these trends.

Toxic heavy metals have increased in Auckland estuaries and micro-biological contamination of swimming beaches has become more frequent. Fish stocks have declined. Infrastructure continues to be built into the sea. Marine Reserves are no longer being created.

In the Firth, the rivers of the Hauraki Plains are delivering high levels of both sediment and nitrogen/phosphorus with impacts well beyond its boundaries.

After the first three disturbing reports the Forum set itself the task of finding solutions. In 2013 Sea Change – Tai Timu, Tai Pari, came into being. It comprised 14 stakeholder working groups – agencies, community groups and aqua-culturists among them – tasked with producing The Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan for the integrated management of Tikapa Moana /Te Moana-nui-a-Toi.

The plan was delivered on 6 December 2016 along with the hope that it would be ‘a catalyst for manuawhenua, communities and agencies to work together to return the Gulf to a place that is vibrant with life, has a strong mauri, is productive and supports healthy and prosperous communities.’

The Spatial Plan is ambitious in intent, concerning itself with ecological restoration to a pre-European state rather than maintaining the status quo.

The plan identifies two major ecosystem components and associated organisms which have been lost but could be recoverable and could do much to assist the rehabilitation of the Gulf.

Mussel beds, both green-lipped and horse mussels, once dominated the sub-tidal regions of the Gulf, covering maybe 1000 sq km, filtering the waters for plankton and removing sediment. By the 1960s commercial exploitation had destroyed these mussel reefs.

Eelgrass beds, and the communities they support, would once have been widely present inter-tidally, consolidating sediment and contributing to clear water. Today eelgrass beds persist in small areas but they are not thriving.

The natural rate of sediment accumulation in the Firth prior to human impact was around 1mm a year and this, cores show, was of coarse material. But 150 years ago finer, mud-like rather than sandy, sediments started to enter the Firth. Most deposited but part remained suspended in the water interfering with light transmission. Eelgrass struggles to survive when sediment accumulation rates rise and reduce the light reaching their leaves.

Some work has been done to restore both mussel beds and eelgrass – for example, Ngati Whatua has a project to revive the old mussel beds in Okahu Bay and artificial eelgrass beds have been created in places like the Whangapoua Harbour – but a much bigger effort will be required to turn back the clock.

Sediment hasn’t just affected eelgrass. It also has major impacts on benthic fauna. Back in the 1940s the Ministry of Works noted complaints about the loss of cockle beds in the lower Firth. Now benthic surveys show a change toward mud-tolerant fauna.

Human activity has increased siltation by an order of magnitude. In the 40 years prior to 1918, 44 million cubic metres of sediment entered the Firth. At first this was due to gold miners seeking gold-rich quartz veins who de-forested the Coromandel Range with fire and, in the absence of vegetation, the topsoil ended up in the Firth.

But from 1908 on much of the sediment came from draining the wetlands that once made up much of the Hauraki Plains. Today sediment continues to enter the Firth, carried from the intensive agricultural region that the plains became, now being home to 410,000 dairy cows.

Nutrient inflow to the Firth maintains elevated year-round levels of phyto-plankton. Between 2006-2015 an average annual load of 3,666 tonnes of nitrogenous material was delivered by the rivers of the Hauraki Plains.

Some encouragement can be taken from the fact that during that period nitrogen input declined by 1.2% a year. But, by way of indicating how far there is to go, the largest Auckland sewage treatment plant discharging into the Gulf releases between 179 and 226 tonnes of nitrogen each year.

Furthermore, in 2011 aquaculture reforms allowed for an additional 1,100 tonnes of nitrogen to be discharged each year from proposed fin-fish farming enterprises. This hasn’t happened yet but if it did dairy farmers on the Plains might feel aggrieved about their efforts at mitigation being cancelled out so wilfully.

The Waikato Regional Council monitors river systems but not the Firth waters. However, NIWA monitored the outer Firth for a period up until 2012. That has revealed that the sea in this region is stratified. At a depth of around 8 metres the temperature suddenly declines, indicating that it is not mixing with surface waters. In autumn dissolved oxygen reaches levels described as deleterious. At the same time the water becomes more acid due to the release of carbon dioxide from the decay of dead phytoplankton raining from above.

Unexplained, is the rise of nitrogen levels in the Upper Firth at a time when nitrogen amounts entering the lower Firth are falling incrementally. One possible reason is that the Firth has passed the point where it can return all the incoming nitrogenous materials to the atmosphere as harmless nitrogen gas.

The Spatial Plan has defined the approaches needed to deal with the varied problems of the Gulf. These solutions require progressive timelines of a multi-generational nature. The Hauraki Forum now has the task of persuading the decision makers to implement the cures. For this to happen, the Forum says, ‘integrated management is seen as an essential fix to ad hoc and ineffective decision making’.

Unfortunately, The State of Our Gulf identifies lack of integration across agencies and the regulations under which they must act is identified as a key issue delaying progress. For example, the report states, ‘The Fisheries Act resource utilisation objectives are directly in conflict with the objectives of the Hauraki Marine Park Act.’

Furthermore, it says, even within the Forum itself, ‘The Crown representatives do not appear to have worked together in any integrated way. This siloed, single-issue approach has militated against the achievement of integrated management. More direct intervention at the ministerial level could lead to more constructive input from the Crown.’

In their foreword to The State of our Gulf 2017 Forum chair, Mayor John Tregidga, and deputy chair, Liane Ngamane, have made it clear that little progress is being made across the key areas and made passionate appeals for help to the new Government, and especially the new Minister of Conservation (see opposite page).

A common approach to life is to say, ‘If it ain’t broke don’t fix it.’ Given the continuing deterioration of so many of the environmental indicators, it seems fair to conclude that the Hauraki Gulf is well on the way to being broken. That being the case, another management approach seems an absolute necessity. Given the integrated nature of ecosystems it seems eminently sensible to try an approach that reflects this.

Fingers crossed that it will happen before there are no longer any godwits needing a haven here during the Arctic winters.

A jewel worthy of protection

The need to give greater protection to the Hauraki Gulf, including the Firth of Thames, was formally recognised by Parliament with the passing of the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act on 27 February 2000.

The Park encompasses 1.2 million hectares of marine environment; the catchments that feed into it, the most significant being the rivers of the Hauraki Plains; a huge rural area extending as far north as Waipu Cove; the urban sprawl of Auckland City, home to a third of New Zealand’s population; Waitemata Harbour, on which the city was founded; over 50 islands; the Coromandel Peninsula; and five marine reserves.

The intention of the Act was to achieve integrated management of the whole area, uniting in a common cause the various agencies involved with management of the economic, natural, recreational and environmental aspects of the Gulf. A considerable challenge but one that the promoters of the new park hoped could be met over the coming years.

The management challenges arise from the competing uses of the Gulf. Each year it generates $2.7 billion dollars of economic activity. Auckland being a port city, some of this comes from marine transport. More arises from fishing and aquaculture. The largest contributors, however, are tourism and recreation. The park also has rich biodiversity, predator-free islands, many endemic seabird species and marine mammals, as well as a significant Ramsar site in the Firth.

The Gulf is of profound cultural and spiritual significance to local iwi who have lived on its shores for many centuries and are keen to see it restored to its former glory.

Forum leaders’ plea to new Government:

Forum leaders’ plea to new Government:

‘Minister, the Hauraki Gulf needs help’

The chair of the Hauraki Gulf Forum, John Tregidga (top left), and deputy chair, Liane Ngamane, (below left), have used the triennial State of our Gulf 2017 report to make personal appeals for help to the Government of Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern (top right) and especially to new Conservation Minister Eugenie Sage (below right).

The two leaders of the Forum have identified several key areas where urgent Government action is needed:

Water quality

John Tregidga and Liane Ngamane note in their foreword that, ‘Water quality degradation is one of the most universally unmet costs of development of rural, urban and mining activity in the Hauraki Gulf catchments. Sediments, nutrients, heavy metals, pathogens, micro-plastics and rubbish accumulate in stormwater discharges, streams and rivers, estuaries and Hauraki Gulf.’

This will only be dealt with if there is ‘a more integrated, comprehensive and less piecemeal approach to regulation and performance . . . We would appreciate some Ministerial advice on innovative options for a long-term approach to their resolution.’

Fish stocks

Estimates suggest that Hauraki Gulf today supports less than 45% of the biomass present in 1925. Snapper and Rock Lobster populations are well below target stock levels, while John Dory, Porae, Gurnard and Trevally population levels are of concern.

On this the two leaders say, ‘We support a fundamental review of fisheries legislation to focus on transparency of decision-making and the abundance and well-being of fish and their habitats, so that the fisheries legislation gives better effect to the objectives of the HGMPA, as was originally envisaged.’

Marine reserves

Only 0.3 per cent of the Hauraki Gulf is protected by statute. There are six marine reserves but only one has been created in this century. For most of this period the Marine Reserves Act has been under review, promising a more appropriate legal framework, but that has not yet been delivered.

The plea on this is urgent. ‘Minister, we urge that you give priority to progressing new marine protected areas legislation, and its implementation. The Forum stands ready to assist in any way it can.’

Ocean sprawl

Historically, the report notes, the main source of ocean sprawl was from Ports of Auckland. Today, however, the sprawl comes largely from shellfish and fish farming. Since 2014 nearly 4000ha of marine space has been consented for mussel and oyster farms or fish farms. In addition, three new marinas or marina extensions have been consented in the period 2014-17, and a dozen jetties and boat ramps approved.

The leaders say, ‘Minister, we urge action on these matters relating to encroachments into the Hauraki Gulf before they become the subject of conflict.’

Tangata whenua

The leaders say, ‘We would welcome the opportunity to discuss the potential for all three Ministers with Maori portfolios to play a leadership role in the Forum, and assist in addressing some issues, particularly those related to fishing, marine protected areas, and any proposals for a recreational park in the Hauraki Gulf.’

Integrated Management

The holistic strategy proposed by the Forum ‘will probably fail because it has no legal status, is therefore unenforceable and given the scale of the implementation task, is probably unfundable, at least under present arrangements. Formal responses from Government Departments have been slow . . . If the new Government sought to remedy these problems the Forum could actively contribute its learnings to a workable solution.’

The Crown and the Forum

‘The Hauraki Gulf Forum was envisaged as an assembly of decision-makers, whose decisions collectively affected the Gulf. The Crown is represented on the Forum by representatives appointed by the Ministers of Conservation, Fisheries and Maori Affairs. The Forum could not be described as a meeting place where representatives worked together to solve shared problems. Rather, the officials attending appear as passive reporters of ministry actions or advocates for single issue policies. We would welcome the direct involvement of Ministers at the Forum meetings.’

Integrated funding

‘We would be interested to discuss whether Government has any appetite for a joint Hauraki Gulf Marine Park fund to advance work on Gulf strategic issues. Minister, could we, through you, discuss possible new financial mechanisms for Crown work related to the Hauraki Gulf with other Ministers including the Minister of Finance?’

America’s Cup opportunities

The 36th Americas Cup Regatta will be an opportunity to showcase the Gulf, its natural and cultural resources and their management, to the world. Minister, we are keen to explore with you and your colleagues how an ethical government investment strategy in the well-being of the Gulf, in this term, might support the investment in the regatta event.’