Pūkorokoro Miranda News – November 2021 Issue 122

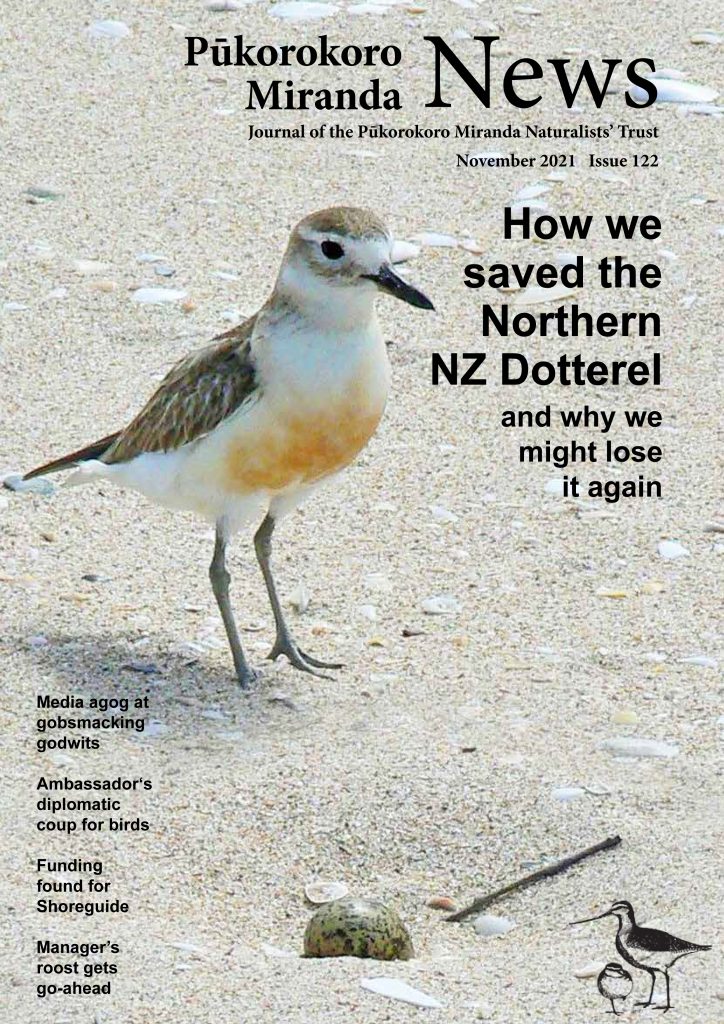

This issue includes a dive into the history of the efforts to save the Northern New Zealand Dotterel, a summary of the latest record breaking godwit migrations this season plus more news and updates.

The management programme for the Northern New Zealand Dotterel/Tūturiwhatu, which has seen the population go from a steady decline to almost doubling in 30 years, is one of our greatest conservation successes. That triumph is due to the work of scores of community volunteers, the enthusiasm of a few dedicated wildlife rangers and the strategy devised by Dr John Dowding, writes Jim Eagles.

One of the particular challenges when it comes to the Northern New Zealand Dotterel is getting an accurate idea of population size – and whether it is changing – because the birds are so widely dispersed.

Early details about the species are extremely sparse. There are hints the NNZD may once have been scattered thinly around most of the North Island and possibly even parts of the South. In one of the few early reports, Walter Buller wrote in 1888 that the species was ‘dispersed along the whole of our shores’ but was ‘nowhere very plentiful’.

In a paper on NNZD written for the recent special wader issue of Notornis, dotterel researcher Dr John Dowding concluded, ‘Its range before the end of the 19th century is not clear, but in the 20th century and until about 1950 its breeding range was apparently confined to northern areas from North Cape south to the Waikato Coast in the west and southern Coromandel Peninsula in the east. . . The population may never have been large.’

The first attempt to estimate numbers did not come until the late 1960s when AT Edgar recorded 1,114 birds but considered this was probably an underestimate. About 20 years later Sylvia Reed did another count and reached a total of 1,024, commenting, ‘Allowing for birds missed from counting and areas not surveyed the population appears fairly static.’ She added, ‘A species with a total population of fewer than 1,400 is surely entitled to be classed as “ endangered”.’

By the 1970s and 1980s, observations of NNZD at individual sites indicated that the numbers were declining, due to their vulnerability to predators, flooding of nests, coastal development and disturbance from humans and dogs.

This led to dotterel protection work starting in several areas, especially around the Coromandel Peninsula and Auckland, involving a mix of community groups. Forest & Bird, the Ornithological Society (OSNZ), the Wildlife Service and its successor the Department of Conservation.

In 1991 DOC set up a recovery group with John Dowding as its scientific adviser. In 1993 a five-year recovery plan, written by John, was formally adopted. In several areas the department appointed rangers to coordinate dotterel work and some regional councils did the same.

The management techniques, which were regularly tweaked in the light of experience, basically involved marking off dotterel nesting sites with fences and signs, having volunteer minders nearby to persuade people and dogs not to disturb the birds and carrying out predator control. Many of the volunteers attended the Dotterel Management Courses the Shorebird Centre has run since 2003 and which have trained about 300 people. It is now estimated that the programme covers about 30% of the NNZD population.

From the outset, local counts indicated that bird numbers were increasing in the areas under management, but it was difficult to be sure of the overall impact. To get more solid evidence, in 1989, 1996, 2004 and 2011, special NNZD censuses were organised as a joint project of OSNZ and the Department of Conservation.

They were held in October, when the birds tend to stay put, and held as far as possible on a single weekend and within two hours of high tide. Counts were done at sites known from past records and at other areas with suitable habitat. If a site was missed or the count was widely different to previous figures a follow up was organised as soon as possible afterwards. Over the years the number of sites counted increased, mainly due to population growth pushing birds into new areas.

John’s paper for Notornis reported that the four censuses showed a consistent and significant population increase. Between the 1989 and 1996 censuses the number of birds counted rose by 10.3%; between 1996 and 2004 by 18.2%; and between 2004 and 2011 by 23.7%. Over all, during the 22-year period of the census the number of birds actually counted rose from about 1,320 to about 2,130, an increase of about 60%, and in the Coromandel by an amazing 254%.

Taking into account the fact that the number of sites being counted was increasing, it was calculated that between 1989 and 2011 the NNZD population rose by almost 50%.

Needless to say, doing a total count of a very widely dispersed bird like the NNZD was not easy, but by the end of the period John felt sufficient knowledge had accumulated to conclude that ‘the two most recent counts are believed to be very close to complete and to provide a good estimate of the population size’.

In addition, he observed, if the rate of increase recorded between the 2004 and 2011 censuses continued, by last year the population would have reached 2,600 birds. The long-term goal of the 2007 dotterel management plan was for a population of at least 2,200 by 2030, meaning that ‘the recovery plan target has almost certainly been well exceeded already’.

John also concluded, that the census data ‘provides compelling evidence for the effectiveness of the management prescription at a regional scale and over more than two decades.’

As well as the overall increase in numbers, the censuses showed that:

*The highest growth in dotterel numbers was recorded in Auckland and Coromandel which are also the two regions with the highest proportion of pairs under management.

*Using data from the Edgar and Reed counts it was found that between 1967 and 2011 the proportion of the population on the west coast declined from 38% to 15%, while that in the more highly managed east coast rose from 62% to 85%.

*Population pressure is resulting in the northern dotterel expanding its range southwards down the east coast into Hawke’s Bay and Wairarapa, and on the west coast into Taranaki. ‘The expansion of range down the east coast in such a short time has been amazing,’ says John. ‘and NNZD are now breeding close to Cook Strait. I find it exciting that the species could soon leap the strait and start breeding in the South Island for the first time in over a century.’

Summing up the success of the dotterel programme, John says there are two particularly significant features. ‘The first is that it was achieved on the mainland.

Many of our conservation successes have been on islands free of predators and with few or no people, but this one was carried off in the face of a full suite of predators and high levels of disturbance from people, dogs, and vehicles.

‘The second is that in the past 15-20 years the on-the-ground work has been undertaken almost entirely by the community. Not all species are amenable to community management, but this one clearly is.’

Unfortunately, there are now growing doubts about whether that amazing story will be able to continue into the future, because it seems the programme has become the victim of its own success.

Because of the population recovery, the northern dotterel’s threat level has been dropped from Threatened to an At-Risk category, meaning the bird is no longer a high priority. In 2006 the New Zealand Dotterel Recovery Group, which had guided the protection work, was disbanded. In 2014 the latest dotterel recovery plan expired, and DOC decided not to proceed with a new one.

As a result, instead of ending on a triumphant note, John Dowding’s paper finishes with a warning. ‘It is important to note . . . that the NNZD remains Conservation Dependent. Management needs to be maintained in core areas, increased in some areas on the west coast, and established at sites in newly colonised regions.’

Privately he adds, ‘The Department does still provide support to community groups at a local level in some areas (particularly Coromandel) with traps, fencing materials, signs and advice. What DOC is no longer doing is coordinating research and management at a national level and planning for the future. I worry that there’s no longer any overall direction. When circumstances change, who will take charge of the response?’

Finally, the paper noted, there were fresh hazards facing the northern dotterel. The east coast between Cape Reinga and East Cape, where 81% of the dotterels now live, is ‘experiencing increasing development and increasing levels of recreational use. Both have the potential to degrade dotterel habitat. . .

‘In addition, climate change is bringing rising sea levels and a higher frequency of storm events, and these are likely to have direct and indirect negative impacts on coastal bird species.’

In other words, there is a risk that in the absence of continued national support the gains made in northern dotterel numbers could gradually be lost. Indeed, John Dowding says, ‘modelling shows that the NNZD population would decline by about 1% a year without any management’.

You can read the full magazine including the other two articles about the Northern New Zealand Dotterel here.

Learning how to save the Dotterel

Helping Dotterel survive in the big city