Pūkorokoro Miranda News – May 2021 Issue 120

An interesting look into the New Zealand history of the Caspian Tern, the largest tern in the world, and a dive into their irregular breeding habits and vulnerabilities.

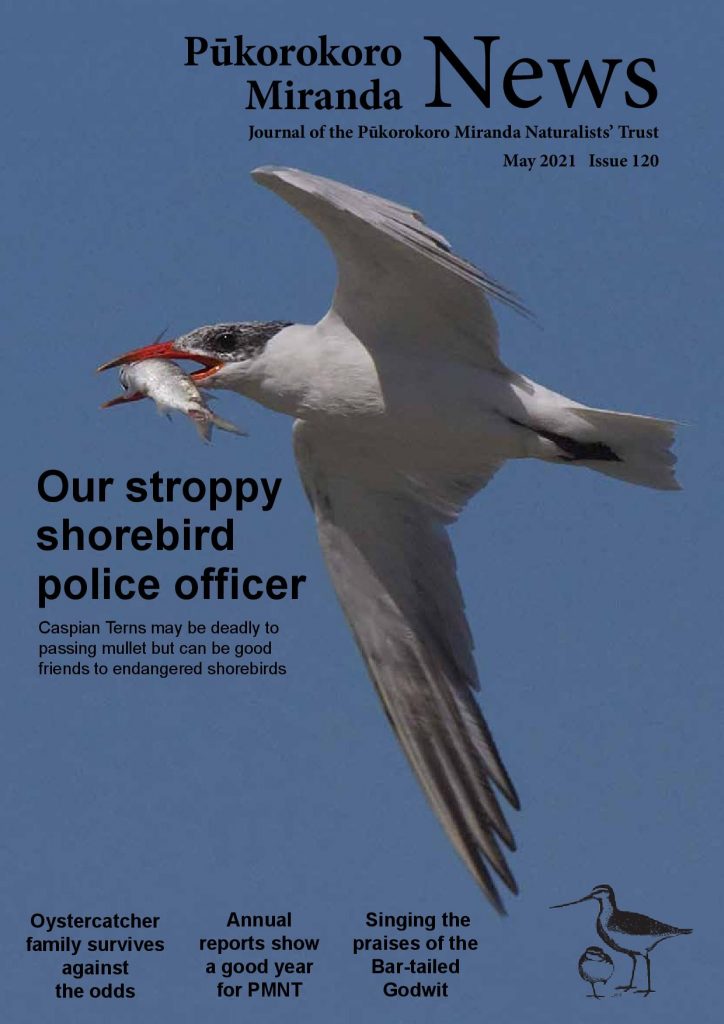

Caspians Terns are big and stroppy . . . with good reason

Caspian Terns are formidable defenders of their nests – and those of other species – but their roosts are highly vulnerable to changing currents and human intrusions so they’re often on the move, writes Jim Eagles.

I’ve always felt Caspian Terns have an air of danger and excitement about them. They remind me of the World War II German Stukas, sleek but deadly dive bombers that appear out of nowhere leaving havoc in their wake. They hunt by cruising along about 15m above the surface of the water, then dive sharply into the water to grab an unsuspecting piper or mullet in that powerful beak, often swallowing it whole.

Even sitting quietly on the shellbank at Pūkorokoro they look tough and aggressive. They’re surprisingly big birds, the largest terns in the world, with wingspans of over a metre and four times the weight of their cousins the White-fronted Terns.

Like the Stuka, their name has a German origin. They were named by Peter Simon Pallas, a pioneer Prussian botanist and zoologist, who was invited by Catherine the Great to be a professor at her St Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Thereafter Pallas spent many years leading expeditions across her vast empire to collect and identify new species. During one in 1770 he saw large terns on the Caspian Sea and called them Hydroprogne (a mix of the Greek word for water and the Latin name for swallow) and caspia (for the Caspian Sea).

Maori gave them the much simpler – but still taxonomically accurate – name of Taranui or big tern (Tara being the name for the White-fronted Tern and Taraiti for both Fairy and Little Terns).

Unlike Terek Sandpipers, which apparently never visit the Terek River, Caspian Terns do frequent their eponymous sea. But they also breed on the ocean and lake coasts of a wide swathe of the planet, including parts of North America, Europe, Africa, Australia and New Zealand, in fact all continents except South America and Antarctica.

The New Zealand, Australian and African birds are essentially resident but those breeding elsewhere make quite long migratory journeys during the non-breeding season.

The global population is estimated at 50,000 breeding pairs and is generally regarded as stable apart from in the Baltic Sea where it is declining.

New Zealand’s Caspian Terns are, similarly, spread out along our coasts and lake shores, with a few large colonies and lots of isolated breeding pairs. They are widely seen but nevertheless regarded as Uncommon and their conservation status is Nationally Vulnerable.

Caspian Terns ‘were apparently so scarce that for 90 years they escaped the notice of the early European ornithologists.’

Dick Sibson, Notornis no39 1992

They are also classified as Native birds but they may not have been in this country as long as you might think. In a fascinating article (published in Notornis No 39 in 1992) Dick Sibson noted a surprising lack of references to Caspian Terns in early accounts of New Zealand bird life. In fact, he wrote, Caspian Terns ‘were apparently so scarce that for 90 years they escaped the notice of the early European ornithologists.’

Furthermore, he said, archaeologists had assured him that ‘very few bone fragments [of Caspian Tern] have been identified from middens, whereas midden deposits yield widespread evidence that White-fronted Terns and our three native gulls [Southern Black-backed Gull, Red-billed Gull and Black-billed Gull] frequently formed part of the Polynesian diet’.

There were, Dick suggested, two possible explanations for this: It could be that ‘like some other waterfowl – eg Pukeko, White-faced Heron, Royal Spoonbill – [the Caspian Tern] is a comparative newcomer to New Zealand and has enjoyed a boom period in the middle of the 20th century’.

Alternatively, he said, the explanation could be that Caspian Terns ‘laid large palatable eggs in places that were usually accessible [and] had become scarce after 800 years of hungry human (Polynesian) predation. When in the spring of 1939 I was taken to see the extensive breeding site in the Mangawhai sandhills, there was ample evidence of Polynesian occupation in the form of cracked cooking stones and fragments of stone artifacts.’

Indeed, he acknowledged,‘ Polynesians were not the only nest-robbers; for as GA Buddle (1951) wrote, “In earlier days it was the local custom to raid the colony when laying commenced in early November, to obtain a supply of eggs for baking the Christmas cakes.”’

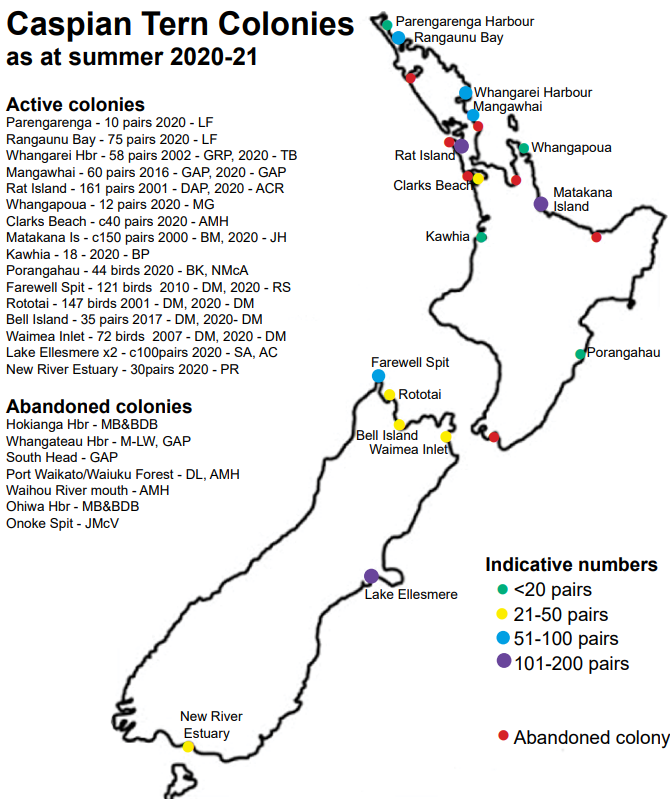

Whatever the explanation, there still aren’t all that many of them. In 1971-75 and 1991-95 Mike and Brian Bell carried out surveys of the Caspian Tern population (reported in Notornis No 55 in 2008) both of which came up with figures of around 1,200 breeding pairs.

Within that seemingly stable population there was, however, considerable movement. Of the 16 breeding colonies the Bells identified in the 1970s, six had disappeared by the 90s and two had a greatly reduced number of pairs. To balance that, one colony had expanded considerably and eight new colonies had been identified.

The second survey also revealed significant geographical movement over the intervening decade with the population declining in the Far North and new colonies forming in the south. In particular, the number of breeding pairs in the Far North declined by 53% and in South Auckland by 35%, but nearly doubled in Northland, Bay of Plenty and Southland.

The Bells suggested that similar surveys of Caspian Tern colonies should be done every 10 years or so but this seems not to have happened. So, some 25 years on, I have endeavoured to update their work using their map of colonies in the 1990s as a baseline.

Like them I contacted birders – mostly Birds NZ regional representatives – around the country to see if the colonies the Bells recorded were still there, whether any had been abandoned and whether any new ones had been created. Where colonies were identified I endeavoured to track down the most recent count and, if this was quite old, sought eyewitness confirmation that the colony was still viable during the 2020-21 breeding season.

This information confirmed that the Caspian Tern scene is extremely fluid. Colonies perpetually rise and fall and sometimes sites are abandoned altogether; when this happens the breeding pairs may scatter far and wide or most may go to a new colony not far away.

Many Caspian Terns do not nest in colonies and they seem to be similarly changeable, sometimes nesting alone or with 2-3 other pairs; often using the same site for years, but just as often moving on after a season.

Furthermore, because they frequently nest in inaccessible places it seems more than likely that there are colonies that even diligent surveyors don’t know about.

As well as the six colonies the Bells identified as having disappeared between the 70s and the 90s, I was told of colonies having been abandoned at the South Head of the Kaipara Harbour, Port Waikato/Waiuku Forest the Waihou River mouth, Whangateau Harbour and Onoke Spit. Meanwhile new (or previously unreported) colonies have been identified at Rat Island in the Kaipara, Clarks Beach on the Manukau and Rototai in Golden Bay.

‘The birds were eventually found nesting in a pine forest near where sand was being mined for iron’

david lawrie, PM News no94

This pattern is well illustrated by the history of the one at Port Waikato. In an article written for PM News No 94, David Lawrie recalled that, ‘In the 1980s an island formed in the centre of the [Waikato] river mouth which provided a safe breeding ground for a large colony of Caspian Terns and also Blackbacked Gulls, Variable Oystercatchers and NZ Dotterels. But in the 2000s the island was slowly eroded away as the river moved further north and by 2004 the tern colony was abandoned. The birds were eventually found nesting in a pine forest near where sand was being mined for the iron.’

Tony Habraken, who regularly monitored the new site, says NZ Steel ‘always accommodated the birds and managed the mining work around the birds’ activities. We are hugely grateful at the way they took it upon themselves to care for the colony and leave it undisturbed during breeding seasons.’ That effort obviously paid off because at its peak in 2011 there were 75 pairs breeding in the forest.

However, for some reason in the years after that the colony split with many of the birds gradually moving 25km further north to a sandbank at Clark’s Beach, on the Manukau Harbour, where there had always been one or two pairs of Caspian Terns.

By 2016 there were only 30 birds at the mine site while a count at Clarks Beach found 31 nests. Before long there were none breeding in the forest while on census day 2020 Clark’s Beach had 82 birds. ‘It is unclear where the missing birds went,’ Tony says. ‘What I can tell you is that they appear to have moved to the Manukau Harbour where breeding numbers have increased at several sites since the decline of breeding at Port Waikato.’

In 2014 a group led by Karen Opie tried to attract Caspian Terns to nest on the sandspit on the southern side of the Waikato River mouth where a large area was fenced off to try to restrict human activity. They carved and painted several polystyrene decoys to be placed within the fenced area and arranged for Caspian Tern colony calls to be played through a speaker system. ‘When the decoys were placed on the spit with the sound equipment there was an immediate result,’ David reported. ‘Within half an hour there were birds roosting in the vicinity and groups of Caspian Terns were regularly being seen in the area. But unfortunately none of them nested.’

Changes in tides and currents do appear to be the biggest threat to Caspian Tern colonies but human behaviour is also a significant problem. Certainly that may well have been the major factor behind the demise of the colony on Papakanui Spit, on the South Head of the Kaipara Harbour, which 50 years ago was one of the biggest in the country with 200-plus pairs.

These days the end of the spit is an island, but Gwenda Pulham recalls that when she started birding there it was one long, continuous sandspit and ‘the fishing vehicles could drive up Muriwai Beach and along the top of the ridge to avoid wet sand and get to the very tip of the spit where I guess the fish were most prolific.

‘Unfortunately the birds were clever enough to also want to put their nests on the highest point of the sandspit to protect them from the waves so the colony, with eggs and chicks and nesting birds, would regularly get driven over. I remember going there once with the late Sylvia Reed and it was carnage. The colony was criss-crossed with tyre tracks and dead birds. I’m not the only person to strongly suspect that this regular disturbance was enough to cause them to go and find somewhere else.’

A perusal of the Classified Summarised Notes published in Notornis suggests that happened very quickly. In 1982-83 Michael Taylor reported 160 nests there. And in 1983-84 D Riddell reported ‘colony didn’t form’.

Gwenda recalls, ‘We didn’t know where they’d gone, there was just no colony, and then Brigid and Kane Glass went sailing and found a colony east of Shelly Beach on Rat Island/Tuhimata.’ A count in 2001 recorded 161 nests with 104 chicks, indicating that that most of the colony had moved to the new site.

A more positive example of the challenges facing Caspian Tern colonies comes from a chenier island in Whangapoua Harbour, on the Coromandel Peninsula, where ecologists Meg Graeme and Hamish Kendall have been working to overcome problems of rats, introduced weeds and erosion.

Meg says that their general observations indicate that the colony has fluctuated in size over time but the work they have done – aided by the island itself becoming more stable and supporting a variety of estuarine vegetation communities – does seem to have helped.

‘Prior to this season’s nesting we cleared an expanse of spinifex that was covering much of the available beach area above high tide the Caspian Terns seem to favour,’ she says. ‘This, as well as the trapping of three large Norway Rats and baiting, has probably helped the colony have a relatively successful breeding season.

‘We have found it very hard to monitor the colony but . . . based on drone photos and a couple of site visits we estimate the colony is about 35 adult birds and that between 20-27 chicks are likely to have fledged. For the next breeding season we intend to clear a larger open high tide beach area and will hopefully have a better drone zoom camera for improved monitoring.’

Looking closer to home, despite their tendency to move around, Caspian Terns are almost always present on the shellbank at Pūkorokoro – often as many as 40 or 50 – and although they aren’t among our signature birds they do provide additional colour and excitement, an important part of what makes the Findlay Reserve such a fascinating place to visit.

However, it’s clear that they rarely breed there. Indeed, the Bell’s maps from the 70s and the 90s record no colonies in the Hauraki Gulf at all.

In the 2000s a good-sized colony did spring up on a new shellbank at the mouth of the Waihou River near Thames but it only lasted about 10 years.

Tony Habraken recalls that when that shellbank developed in 1996 he and Dick Veitch went along to have a look but found no birds then or in the next couple of years. But by 1999 there was at least one pair breeding there and by 2005 he counted 98 birds plus nests and chicks. ‘This typifies how opportunistic the species can be in honing in on suitable real estate/habitat.’

Unfortunately in 2008 high tides washed out the nesting area, leaving eggs on the beach, and the following year there were no Caspian Terns. Some terns were seen there in 2010 though it’s not known if they were breeding but, Tony says, ‘at this point the shellbank had joined the mangrove belt so their security was probably compromised and there are no more records after that’.

It’s unclear where those birds went but a couple may have briefly tried breeding on the Pūkorokoro shellbank. David Lawrie recalls that a few years ago there were often one or two pairs nesting on the shellbank. And Tony’s records show that in 2012 he saw a couple of birds ‘tending to a scrape and displaying the aggressive behaviour typical of nesting’. However, nesting has not been seen there in recent years.

So if we don’t have any breeding colonies nearby where do the birds regularly seen at Pūkorokoro Miranda come from? As the below map of eBird records from the past 12 months shows, when they are not breeding Caspian Terns spread out around the country, not just on the coasts but also lakes and rivers.

As a result, most summers there are at least 40-50 on the shellbank and in March this year 140 were counted. Very likely many of them are pairs that nest in ones or twos around the Hauraki Gulf and get together when breeding is finished. Others probably come from colonies further afield.

Dick Sibson, in the article referred to earlier, noted that there are generally three times as many Caspian Terns seen on the Firth during winter as in summer, and twice as many on the Manukau, which rather confirms that they come here when they’ve finished breeding.

Early banding work, he wrote, ‘has shown that some Caspian Terns from the Northland colonies wander south to winter in [the Firth or the Manukau] or in the inner Waitemata’. Populations of many species of colonial terns were known to fluctuate and ‘a successful nesting season in Northland is likely to be followed by a strong influx into the Firth of Thames or Manukau Harbour, as happened, for example, in the years 1957-60 and 1966-71.’

Dick noted that the early colour-banding work by Maida Barlow at Invercargill had shown that Caspian Terns dispersed northwards after nesting but ‘it remains to be seen how many southern birds reach the vicinity of Auckland.’

The pattern of Caspian Tern movements after nesting is still not entirely clear. I have not been able to get data about them from the Banding Office. However, reports from individual birders suggest that they spread far and wide.

For instance, between 1994 and now Tony Habraken has recorded 33 banded Caspian Terns – comprising at least 12 individuals – in the Firth of Thames. These all originated from Mangawhai and South Kaipara Head (banded by Sylvia Reed and her team) and Bell’s Island near Nelson (by Willie Cook and his team).

Although he hasn’t seen any from Invercargill in the Firth, Tony says he has sighted birds from there, plus a bird from the Ashburton River banded by Ray Pierce, on the Manukau Harbour, ‘so it would not have been beyond them finding the FOT’.

Indeed, the use of engraved leg bands on Caspians from Nelson since 2010 has revealed that some birds from the South Island regularly head north to warmer climes. One such, A29, was spotted by Tony on the Manukau in 2013, and at Kaiaua the following year. Since then it has been recorded at sites from Whakatiwai, north of Kaiaua, to Tararu, north of Thames, in 2014, 2018, 2019 and 2021 which, as Tony says, ‘suggests it has made the FOT its regular wintering ground’. That’s good news for those who like seeing this formidable bird dive bombing for food or chasing away predators like harriers around the Firth of Thames.

Other articles in this issue

A surprise Godwit migration

Updates from the international godwit tracking program that continues to provides fascinating information, contrary to what was previously thought, that a lot of two-year-old birds don’t hang around New Zealand until they’re three of four, they head back north.

Variable fortunes of an Oystercatcher family

The long-running saga of the challenges facing shorebirds using the grassy coastal strip at the southern end of Kaiaua… this time with a happy ending.

There’s more to Glasswort than meets the eye

Olga Bochner explores the fascinating history of Glasswort, or Sarcocornia, the pretty little succulent which lines many of the paths leading to the bird hides.